Introduction

Research of the physiology of senses and perception requires knowing when the stimulus causes a perceptual sensation in the experimental animal. In order to achieve this requirement, the animal should be trained to report its sensations through various experimental tasks. But animal training can constitute some problems – it takes rather long time and it does not always yield accurate reports. Thus, it is preferable to develop a method for studying the animal’s behavior that does not require any training.

Thus, I chose to study a reflexive behavior in the barn owl. This behavior includes reflexive eye movements and pupil dilation as a response to unexpected visual or auditory stimulus. The barn owl is a nocturnal predator. It survives thanks to its ability to detect small prey in dark and noisy environments. It has frontal eyes and stereo vision that use a strategy for information processing of the physical space resembling in many aspects strategies used by mammals and even humans (van der Willigen et al., 2002). However, in the barn owl’s natural habitat the light levels often fall below the threshold level at which it can see its prey. Then the barn owl uses its remarkable sense of hearing to dynamically locate the prey (Payne, 1971). Thus, the specialization of the barn owl in spatial information processing by both senses, vision and audition, makes it an attractive animal model for studying visual-auditory integration and its influence on reflexive behavior.

Previous work that was done in this field showed that pupil dilation can be obtained in an awake, untrained and head-restrained barn owl in response to a sound stimulus. Moreover, it habituates when the sound is repeated and recovers when the frequency or location of the stimulus is changed (Bala and Takahashi, 2000). My research will focus on the effect of visual pop out stimuli, as well as the effect of visual-auditory stimuli, on the reflexive pupil dilation and eye movements.

Research Goals

- The first goal of my research is to develop an automatic tracking system that is able to track the pupil size and the eye movements.

- The second goal is to use the developed system that was mentioned in the first section in order to examine the hypotheses regarding visual selective attention in barn owls. For the hypotheses please see section “Research Hypothesis”.

Research Hypothesis

- The first stimulus type I would try to examine is pop out. My hypothesis is that similarly to humans, the pop out stimulus attracts the barn owl’s attention. This should be expressed in pupil dilation and in movements of the eyes towards the pop out stimulus. For more detailed explanation about the pop out stimulus please see section “Work Plan”.

- The second stimulus type I would try to examine is bimodal oddball. My hypothesis is that visual and auditory information combined together are integrated during the processing in the brain and create a more salient response than when each of the stimuli is presented separately. For more detailed explanation about the bimodal oddball stimulus please see section “Work Plan”.

Methods

Animals

The experimental animals that I use in my research are barn owls (tyto alba). All birds are hatched and raised in captivity and kept in large flying cages that contain perches and nesting boxes. In all of the conducted experiments the subjects were head-restrained and slightly anesthetized by using isoflurane (2%) and nitrous oxide in oxygen (4:5). When it is anesthetized, the bird is put inside a restrainer and its head is fixed to the frame of the restrainer. The restrainer is located at the center of a sound-attenuating booth plated with acoustic foam that is used to suppress echoes. While the bird is kept inside the booth, the isoflurane is removed and the bird is maintained on a fixed mixture of nitrous oxide and oxygen(4:5) (Netser et al., 2010).

For pupil dilation and eye movement measurements I opened one of the bird’s eyes by attaching miniature clips to the small feathers on the eyelids. The clips are gently pulled by strings in order to open the eyelid. This procedure does not prevent the blinking of the nictitating membrane that enables spontaneous moisturizing of the eye.

Experimental setup

For video recording of the change in pupil size I used a Point Grey analog video camera that uses IEEE-1394 interface, which is also called FireWire. Around the lens I placed an infra-red LED ring. Because it is rather difficult to distinguish between the barn owl’s pupil and iris, I project the infra-red light into the bird’s eye and get its reflection from the retina. Since the barn owl’s photoreceptors, like those of humans, are not sensitive to infra-red light, the projection of infra-red light on the owl’s eye is not noticeable by it and thus does not influence the pupil dilation or the eye movements.

The acquired videos during the trials are stored on the computer and are processed offline through MATLAB software.

Pupil dilation data analysis

An automatic tracking software was developed by me and is used to track the pupil during the whole acquired movie (see preliminary results). The algorithm finds automatically the region of interest (ROI) that contains the pupil in the first frame. This is done according to intensity differences between the pupil and its surrounding. My next step is to convert the ROI from a cartesian representation into polar representation. In this polar image I draw a curve that represents the borders of the pupil. I identify these borders using an intensity threshold. Then I apply filters to smooth the curve. In case there are some artifacts, such as feathers that enter the ROI, that distort the curve that was drawn previously, I apply a threshold to this curve and this way I get rid of the artifacts. Afterwards I apply a polynomial fitting to the smoothed curve and then I convert this polynomial from polar representation back into cartesian representation. Next I fit an ellipse to the curve that I got in the cartesian image. It is necessary to fit a geometrical structure to the curve because this way we can calculate all its parameters and learn about the change in pupil size.

Eye movement data analysis

The method that I will be using includes a tiny gold plated neodymium magnet that is implanted in the bird’s eye, under the conjunctiva and a Honeywell HMC1512 magnetic displacement sensor that is mounted on the bird’s skull. This is a single surgical procedure. When the eye moves, the magnet moves with it and the sensor tracks its position. A single sensor chip can reliably track a single dimension of eye movement. Thus, I will start with one chip to track the horizontal dimension. Another optional method for eye movement tracking is to use three reflectors that are glued to the cornea and reflect infra-red light. A video camera will record their movement over time during the trials and this movement will be analyzed by tracking software, whose basic principle is similar to the one described in the previous section.

Work Plan

Plan for first year

- Construction of the experimental setup.

- a. Control the video camera via MATLAB software and synchronize its operation with the stimuli produced during the trial.

- b. Create the experimental circuits that generate the auditory stimuli and define their features, as well as create the visual paradigms that will be projected during the experiments.

- Construction of an automatic algorithm that tracks the size of the pupil across the recorded videos.

- Development of the magnetic eye tracking method.

Plan for second year

Performing the experiments.

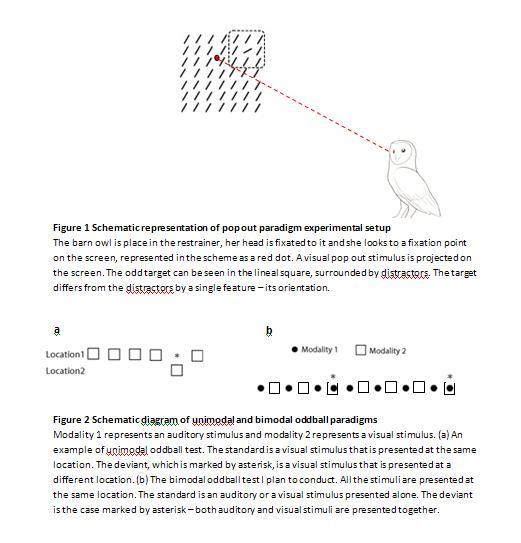

- a. Pop out paradigm. The pop out effect can be expressed during feature search. The observer’s task is to locate an odd target within a field of identical distractors. The target and the distractors are differentiated from one another by a single property, such as color, shape, orientation or size. Humans have mechanisms to abruptly detect the pop out target and are attracted to it (Adler and Orprecio, 2006). The question that I will try to answer in my research is whether a pop out stimulus attracts the barn owl’s attention as well. In order to answer this question I will conduct the experiments as follows. The barn owl will be head-fixated. In front of it will be a screen upon which the visual stimulus will be projected. The stimulus will fill the whole screen. There are three possible setups – the odd target will be on the left side, the odd target will be on the right side or there will be no odd target at all. The last setup will be used as a control. The experimental setup can be observed in Fig. 1. After the experiment I will be analyzing the owl’s eye movements. My expectation is that the owl will produce a reflexive eye movement towards the odd target. I will start with paradigms that contain a high feature contrast between the distractors and the odd target, i.e. big difference in the orientation of those mentioned above. Then, I will decrease this contrast in order to find the threshold needed for the pop out detection and compare it to the one in humans. Afterwards, conduction of additional pop out experiments is possible, such as motion, color, etc.

Bimodal oddball paradigm. Oddball paradigms use a long sequence of stimuli. This sequence contains common stimuli, which are the distractors, and rare stimuli, which are the targets and are hidden within the common stimuli. The bimodal oddball paradigm is commonly used for estimation of human perception in healthy and diseased subjects. It was found that humans find the stimulus that is rarely presented as the salient one and are more attentive to it (Brown et al., 2006). The bimodal oddball paradigm I plan to use in my experiments will contain presentation of two different modalities – visual modality and auditory modality. I will use it in order to investigate the integration of the information, which is received from these two modalities, in the brain, through its influence on attention. My experiment will include a long sequence of common stimuli, which will be individual visual or auditory stimuli, and a rare stimulus that is a combination of both stimuli mentioned above, imbedded inside the common stimuli. Similarly to the work presented by Netser (Netser et al., 2011), where he showed that in auditory adaptation experiments a reflexive eye reaction was observed when a new, unpredicted sound was presented to the owl and “surprised” it, I expect to see in my experiments similar reflexive reaction to the rarely presented stimulus, i.e. to the combined visual-auditory stimulus. Also, I plan to examine whether the bimodal stimulus is more salient than a unimodal one, e.g. visual or auditory stimulus alone, whose location rarely varies. A unimodal experiment is illustrated in Fig. 2a and the bimodal experiment I will be conducting is illustrated in Fig. 2b.

PROJECT LEADER: Inna Yarin

References